The detectives who investigate food poisoning mysteries

Features correspondent

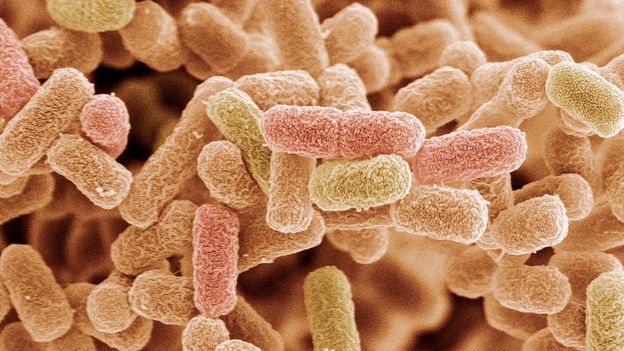

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibrarySome killers are so small they need to be hunted with a microscope. Veronique Greenwood talks to an investigator tackling baffling outbreaks of contaminated food.

It was in December 2015 that the cases began to trickle in across the US. There were never very many at a time, but they were consistent: the victims, whose symptoms may have included vomiting and bloody diarrhoea, were testing positive for specific, nasty strains of E. coli. And the patients were all over the place – there were cases in 20 states by the time the Centers for Disease Control issued the first outbreak announcement, with 10 people taken to hospital. It appeared that the E. coli was in something they ate, and the CDC, with local and state health agencies, put investigators on the trail.

While most people might not realise it, a spot of food poisoning can be serious business, and it is often not an isolated affair. In the worst cases, it can be lethal. Finding the source of the outbreak, and dealing with the root cause – contamination in a slaughterhouse or poor hygiene at a produce-packing plant, for example – is key to making us safer in the future. The story of the E. coli outbreak that began in winter 2015 is a window into the real-life CSI: Your Kitchen Cupboard, the work of the food detectives tasked with ensuring the public’s health – which begins, of course, with arriving on the scene, and asking questions.

iStock

iStockWhat had patients been eating before they got sick? Could they remember what they bought at the grocery store in the week leading to the illness? Did they have a frequent shopper card that investigators could use to find out from the store what they bought? For each patient, a public health investigator spends 30 or 40 minutes on a standard interview questionnaire, explains Ian Williams, chief of the CDC’s Outbreak Response and Prevention Branch. The aim is to find foods that link the patients.

Sometimes they all ate peanut butter sandwiches. Or they all had a beet salad. But in this case, he says, “when we did the interviewing with the standard questionnaire, there was nothing coming out of it.” There were also certain odd details about the outbreak. Nearly 80% of the patients were women.

The CDC had sequenced the entire genome of each patient’s E. coli – a relatively new and powerful strategy for them – and the DNA fingerprints were identical, or nearly so. That meant that the infections were being caused by the same source. But what could it be? Meanwhile, the cases kept coming in. “We would have three, four or five cases a week for week after week after week,” says Williams. It was strange. They were so spread out – just a few at time, as if whatever patients were eating was something that had a long shelf-life, or was eaten only every now and then.

Cases appear on investigators’ radar screen when clinical or public health labs, where patients’ samples are tested for bacteria, upload them through a laboratory network called PulseNet. PulseNet was how the CDC realised there must be an outbreak, and it told them that the outbreak was ongoing. But the source was still mysterious.

Here, however, is where the peculiar genius of outbreak investigators came in to play. When the questionnaire doesn’t turn up good leads, the detectives switch into anthropologist mode, asking more opened-ended questions. They get to know the patients as well as they can, learning about their families, what they like to do together, where they go out to eat. They look for patterns. They think about what foods have caused this particular kind of disease in the past. They pay attention to details.

This has often led them to surprising conclusions. For instance, there was an outbreak of salmonella poisoning six years ago that primarily affected children. The questionnaire having turned up nothing useful, the investigators switched modes. And they noticed that many of the patients happened to have aquariums. The outbreak strain was traced not to a food, but to a frog: the African dwarf frog, which the patients had as pets. A call to the breeding company led to an investigation and the end of the outbreak.

iStock

iStockIn the case of the E. coli outbreak, it was also an observation about patients’ habits that helped crack the case. An epidemic intelligence service officer assigned to the case noticed early on that these people –who, again, were mostly women – seemed to do a lot of baking. These strains of E. colihad mostly been seen in raw vegetables and meat, but could they be in, say, flour as well? The trouble was, people tended to put their flour into canisters and get rid of the bag, so it was difficult to say which brands they were using. But the detectives managed to find two bags of Gold Medal Flour in patients’ homes in different states. They were produced at the same mill in Kansas City, Missouri, just one day apart.

Then, “the thing that really kind of broke this open for us,” says Williams, “was that there were three children who ate at three different locations of a Mexican-style restaurant chain.” At this chain, while families were waiting for their food, the restaurant staff would often give children a ball of tortilla dough to play with. All the kids had played with the dough, and one had even eaten it. “Where did the flour that made that tortilla dough come from?” says Williams. “It actually went back to that same mill in Kansas City, produced around the same time.”

After that, the health authorities contacted General Mills, the company that makes Gold Medal Flour, and soon it issued a recall, advising customers to jettison the products made during the suspect period. By the time the outbreak investigation was closed, the E. coli had been confirmed in the flour of several victims, and 63 people had become ill, though luckily, no one had died. And a conversation had begun about flour, says Williams.

Usually, you would expect flour to be cooked before it’s eaten. And you wouldn’t think a little flour dusted around the kitchen would be a problem. But it is a raw agricultural product, in the end, from farms where there may be animals (which can spread E. coli). And it’s processed in plants where wheat from many different places is ground at once, so one farm’s contamination could have a big effect.

The outbreak serves as a reminder not to eat raw dough or batter. It also suggests that perhaps companies or industry standards may want take into account the fact that people can and do get sick from baking with flour. Treating it as more of a potential danger – paying more attention to contamination, and coming up with new ways to prevent it, from wheat field to mill – may save lives in the future. All in a day’s work, for the food detectives.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.