Striking landscape photos from around the world

Features correspondent

Mark McColl

Mark McCollA new exhibition features some of the world’s leading landscape photographers, with images spanning the globe – from Iceland to Kyrgyzstan. Travel photographer Graeme Green explains the appeal of capturing the natural world.

Life often moves at an unforgiving pace. Deadlines and pressures build up. Days go by in a blur. For many photographers, myself included, landscape photography provides a much-needed opportunity to go outside, to switch off the phone and get away from the daily demands on our time.

It isn’t just the art of photography that’s appealing, but the act of getting out into nature and taking a breather. Working with a camera, taking time to explore and study a landscape, you can create a bit of mental space for yourself. It’s hard to feel stressed when you’re standing in the wilds of Patagonia or on the beaches of the Outer Hebrides.

Joe Cornish

Joe CornishPhotographing landscapes is different from other photographic disciplines. For most of the last 20 years, I’ve been travelling the world with a notepad and camera, from Mexico to Namibia to Cambodia, often moving quickly, producing photos, writing articles, sorting logistics and keeping in contact with editors from the road.

Carla Regler

Carla ReglerThe photography itself can be fast-paced, too, often involving an element of adrenaline. If a gorilla rumbles through the rainforests of Uganda or a whale breaches the surface in Antarctica, you usually only have a moment to get the picture, and that’s all part of the excitement. Likewise, if the job is to photograph a chaotic, teargas-soaked riot in Chile or morning prayers in Bhutan, you have to be alert to the moment and capture unique, fleeting instances when they happen. As much as photographers might wish otherwise, animals and people don’t tend to strike a pose and hold it, at least not in the most engaging kinds of photography.

Damien Demolder

Damien DemolderI particularly enjoy street photography, walking through cities like Havana, Cuba or Oaxaca City in Mexico, catching moments from everyday life. The pleasure and the challenge here is that a picture appears and disappears in an instant. Miss the photo and it’s gone for good.

With landscape photography, the pace is slower. You need to take your time, explore, watch and, usually, wait. It’s been likened to a form of meditation. “The landscape photographer often finds the business of their photography a contemplative and calming one,” landscape photographer Charlie Waite of Light & Land tells me. “I try to convey what I saw and what I felt. What I’ve got to do is evoke in the viewer a sense of relishing human existence.”

Matt Anderson

Matt AndersonWaite is behind a new exhibition in London, Evolving Landscapes, and a new book of the same name, both featuring work from some of the world’s leading landscape photographers, including Joe Cornish, Paul Sanders and Matt Anderson, with images spanning the globe – from Iceland to Kyrgyzstan. Nearly 30 years after Douglas Coupland dedicated his novel Generation X to an “accelerated culture”, the ubiquity of digital technology and the arrival of smartphones, Facebook and Instagram has kept increasing the pace of modern life. “We’re becoming more and more out of sync with the natural rhythm of the Earth,” Charlie suggests. “Photography certainly makes me feel more connected to the world. When I emerge from any pursuit of making a landscape photograph, I feel much more enriched.”

Antony Spencer

Antony SpencerThe photography on show at the OXO Gallery covers locations as far apart as Scotland, Vietnam, Iceland and the USA, ranging from the grand scene to the intimate detail and from classic landscapes shot on traditional film cameras through to abstract images using innovative digital techniques. What unites them, and perhaps almost all landscape photography, is that the pictures required each photographer to step outside of their busy life, to slow down and really soak up a landscape. As Waite puts it: “Landscape photography is very much about noticing and in-depth observation.”

Graeme Green

Graeme GreenOne of my photos that’s part of the exhibition, The Big Sleep, was taken in Gjirokastër, Albania, on a recent expedition teaching landscape photography. We went out at 5am one morning and spent time watching, waiting and occasionally photographing as the sun rose slowly over the city sprawl and the surrounding Gjerë mountains. Rather than the more obvious wide landscape shot of the city, I used a zoom lens and spent time picking out details on the opposite snow-dusted mountains, including deep ravines, radio towers and lines of trees part-hidden by mist.

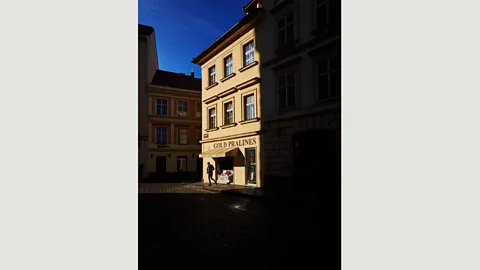

Getting away from emails, social media and pressures on our minds, and allowing ourselves to think about other things, seems increasingly important these days, which might also help explain the growing popularity of landscape photography. Many of the other photographers whose work is featured in Evolving Landscapes would no doubt say the same, whether it’s Phil Malpas capturing dawn breaking at Val d’Orcia in Tuscany, Carla Regler photographing breaking waves in Cornwall, or Damien Demolder waiting for “the golden moment to materialise” on the streets of Prague.

Phil Malpas

Phil MalpasFor his Red Chimneys photo, taken in the Strait of Gibraltar, Waite also had to play a ‘waiting game’. “I became very concerned that there should be just one breaking wave that fell across the entire width of the photograph,” he explains. “Consequently, I was waiting there for some time, such is the capricious nature of waves.”

Charlie Waite

Charlie WaiteNot all photos are taken with such care or patience. Just as the shift from vinyl to CDs and downloads was accused of losing the ‘soul’ of music, there’s often a weary “everyone is a photographer” response from professional photographers to the digital revolution and the glut of photos taken on smartphones or digital cameras and shared across social media, many of them poor and hurriedly taken. Many photos that appear online have also been so heavily edited using computer software that they look awful: unreal scenes with over-saturated colours; foregrounds that don’t match the sky conditions; white halos of light around objects and other effects.

Paul Sanders

Paul SandersBut one of the things Evolving Landscapes looks at is how digital technology has also opened up new techniques to push landscape photography in creative new directions. Paul Sanders’s photo from Tup, Kyrgyzstan, for example, was produced by taking seven vertical shots and then stitching them together in Lightroom to form an epic panorama.

Doug Chinnery

Doug ChinneryDoug Chinnery works with, and teaches workshops on, techniques, such as Intentional Camera Movement (ICM) and multiple exposure (superimposing two exposures or more to create a single image). His photo Argentum Skein, taken at Hodge Close Quarry in Cumbria, is a multiple exposure image, composed of around five frames. “By layering multiple exposures, the feathery nature of the branches were exaggerated and I liked the effect of placing the tree centrally, making the tree the star of the show,” Chinnery explains. “Later, back on the computer, I was able to exaggerate the silver tones in the bark and draw up the wonderful rich reds in the rock face behind to contrast against the web of branches.”

Sam Gregory

Sam GregorySam Gregory is another photographer using technical innovations to explore what’s possible with a camera. His photo Mesozoic X is a macro image taken on Dorset’s Jurassic Coast. But elsewhere in his work, Sam uses ICM, multiple exposures and more. “These new creative approaches allow photographers to move from representational images into something more abstract, or a scene that’s impossible to see with the human eye, by using techniques such as long exposure to render scenes over many seconds or minutes, or macro that shows us the world in amazing close detail,” says Gregory. “With the use of ICM and multiple exposure, landscape photography can push its visual boundaries. I’ve found certain techniques have allowed me to create whole new worlds of abstract images that are truly unique.”

Predicting how those techniques (and others yet to be invented) will feature in landscape photography in 25 years is difficult. But one central element will no doubt remain. “The fundamental impulse to want to photograph landscapes is the same now as it always was,” concludes Waite. “Composition remains at the forefront of people’s concerns. People still very much want to express their human response to the world around them.”

Source link