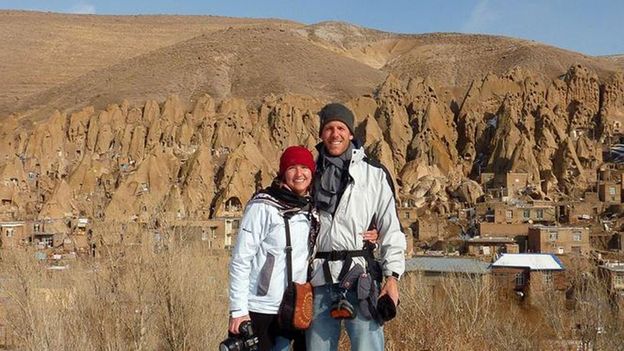

‘How we quit our jobs to travel’

Quitting your job to travel is not only an option for those who go solo. Here is how one couple did it – and how they have stayed on the road, and together, ever since.

When people ask us, “What’s the most frightening thing

you’ve done while travelling the world?”, they often expect a story from Iran,

Kazakhstan or Rwanda. Yet while we have encountered plenty of challenges during

our travels, many of which have been fodder for stories on our blog, our most difficult

moment came before all that. It was when in 2006, as mid-career professionals, my

wife and I handed in our resignation letters, setting aside the security of one

life for the uncertain opportunities of another – together.

Both of us are American, but we were working in Prague

at that time. Audrey, my wife, managed tax and legal issues for US media

organisation Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. I was a management consultant for

the mobile phone provider Vodafone. After five years in Prague, and a combined

20 years of professional experience, we both had begun to feel as though our careers

no longer challenged us. We needed a professional and creative re-boot.

Travelling together wasn’t new to us, having followed

our simple 25-person wedding in Pienza, Italy with a five-month backpacking

trip across Europe. But it was a trip to Thailand over Christmas 2004 that truly

illuminated how we could make long-term travel a reality. Even though we could

have budgeted for a pricier hotel, it was a 400 baht per night bungalow that

brought us joy and satisfaction.

Back home, intrigued by the idea of acquiring life

experiences over objects, we found other ways to adjust our spending habits. We cut back on items for our apartment, clothes and

eating and drinking out. Our goal: to save up for a 12- to

18-month sabbatical that would let us both travel the world and develop skills

that could transition us each into alternate professions – and into the next

stage of our lives together.

The major mitigating factor? We are two people. When

you act alone, you can just pick up and go. As a couple you must constantly

communicate to make sure you’re still aligned in your goals and needs. It’s something

we call “checking in”, a process we’d used somewhat

informally in our daily lives, but now approached more deliberately given the

major life decisions ahead of us. The decisive check-in

happened one night as we sat together at the edge of our bed in Prague, probing

possible reasons for making the leap – or not.

“Are we really ready to do this?” I asked.

“Well… maybe we can put it off just a little while

longer?” Audrey responded, echoing my own ambivalence.

“But one year becomes five, five becomes 10. The next

thing you know you are looking back and wondering ‘What if?’” I said. We looked

at one another, knowing what we were about to do.

Granted, our decision seemed a little unhinged, especially

to those close to us. Luckily, we had prior experience with the challenging

conversations and puzzled looks, having set off five years earlier from San

Francisco to Prague in the mid-winter – with no jobs lined up. It was a

decision that perplexed our friends and family, but also satisfied the nagging

curiosity that we both had.

And so in December 2006, two years after our fateful

Thailand trip, we handed in our resignation letters, sold everything except

what we could cram into our backpacks and departed with two one-way tickets to

Bangkok.

Over the next eight years, we travelled the Silk Road

overland from the Republic of Georgia to China, climbed to the top of Tanzania’s

Mount Kilimanjaro, took a 60-hour train from Iran to Istanbul, witnessed the

sun rise over the salt flats in Bolivia, followed penguins in Antarctica, trekked

in the Himalayas, tracked tigers in Bangladesh and were continually humbled by

the prevailing kindness shown to us by people we met.

That one-year sabbatical? It

became a new lifestyle – and it did lead to different professions.

Our website, Uncornered Market, began as a creative outlet for stories of adventure coupled with tales

of places and people that aren’t usually represented in mainstream media. We

began its development alongside Buddhist monks in internet cafes in Luang

Prabang, Laos, and put the finishing touches on it somewhere in Battambang,

Cambodia. The blog’s success has since led to various brand ambassador gigs, professional

speaking engagements, freelance writing and photography assignments and digital

consulting projects – all of which help fund our continued journeys.

Even so, the big question isn’t how we’ve made our

finances and careers work. It’s how we’ve made our relationship work.

As American writer Alexandra Penney once said, “The

ultimate test of a relationship is to disagree, but to hold hands.” We’d add, “…while

traveling the world and running a business together”.

In some ways, we complement each other well while on

the road. One of us often needs a little push from the other to get past fears

and grow. In early 2007, for instance, Audrey was reluctant to visit

Turkmenistan. She knew from her previous job that it could be a dangerous country

where journalists were incarcerated; some even died in jail. I wanted to take

the risk and see for ourselves. So we decided to leave the decision up to fate,

resting on whether our visa applications were successful.

They were. On our ensuing cross-Caspian Sea ferry from

Baku, Azerbaijan to Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan, Audrey, despite her initial

concerns, was the one who started chatting with other passengers, using the

Russian she had honed from both her previous job and two months of travel in

Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. The next thing we knew, we had arrived, and were

being plied with glasses of vodka and watermelon by Turkmen vacationers on the

beach.

Another difficult challenge was our own expectations.

Ditching what we called the “perfection narrative” of our relationship – the idea that marriages are supposed to be easy

and ideal, when in fact they are full of bumps and hard work as you inch toward

shared goals – was especially freeing. And travel helps. Wake up after a week without

showering in Nepal’s Himalayas and you have a new appreciation for who the

person next to you really is. Later that morning, when that unwashed partner makes

it over a 5,400m mountain pass and motivates you to do the same, you might just

find your heart brimming over with pride.

Still, sometimes we must withdraw to our inner selves

to maintain a level of independence and reflection. Allowing and respecting

this need is especially important when one or both partners happens to be an

introvert, as I am. This is where the ability to create mental space, even in

shared (and small) physical space, can be a relationship-saver. We might sit

next to each other on a 17-hour bus ride without speaking for hours at a clip.

We aren’t angry at one another; instead, we are creating the circumstances we

need to reflect and regenerate for the next adventure.

And yes: there are occasions where we fight, sometimes

to blow-out proportions. One of those times was in Buenos Aires, the night before Valentine’s Day

2010 – and while I don’t recall what we fought about, the argument ended with

us each boarding separate buses, headed in opposite directions, in the middle

of the night. The next morning we reconciled, reflected and even wrote a piece

on how

to travel the world together without killing each other.

Today, we’re often asked for our secrets to travel,

relationships and life satisfaction. Our biggest tip? The greatest impressions

on life’s highlight reel need not always be attached to a several thousand

dollar “trip of a lifetime”, but can instead be found, say, in the eight euro bottle

of wine that you share under a tree behind an old train station on the

France-Switzerland border.

As a couple, meanwhile, our travels have provided us

the opportunity to create a library of shared stories and life experiences. Our

respect and appreciation of our differences has helped us grow together, not

apart. But it’s important to remember that travelling and working together forces issues to the surface; work through

them immediately, rather than letting them stew and simmer.

Oh, and if you board separate

buses, make sure they eventually wind up in the same place.

Source link